Where Ted used to live

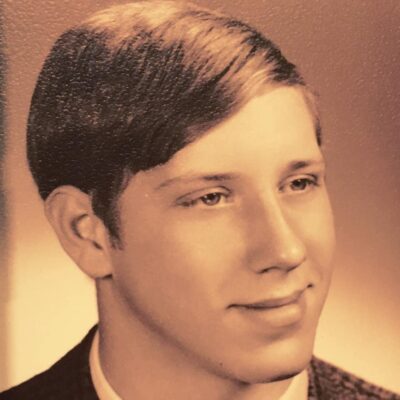

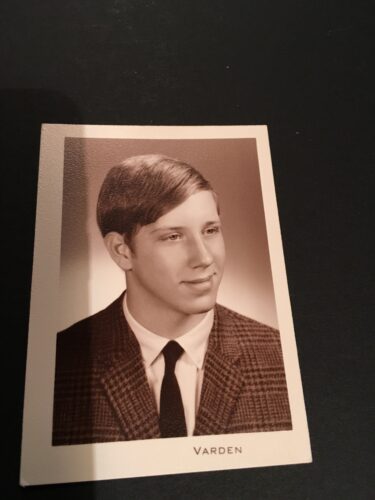

Edward (Ted) Nichols

520A Vermont St

San Francisco, CA 94107

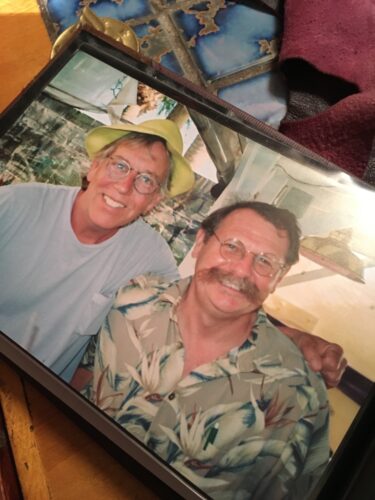

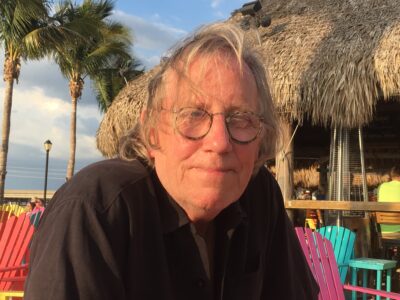

Attached are some photos of Ted. The last six are some good friends from San Francisco who made his life easier toward the end and the front of the house on Vermont St in San Francisco where Ted lived.

Ted Passed away on March 23, 2022

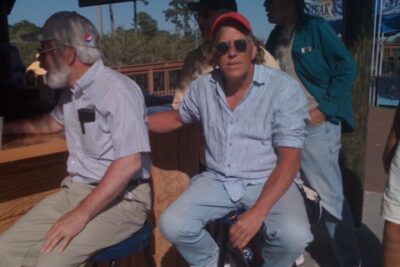

Ted Nichols on the beach at Boca Grande

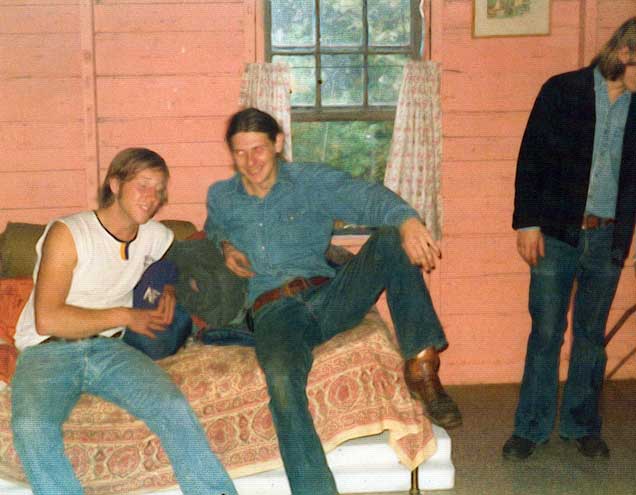

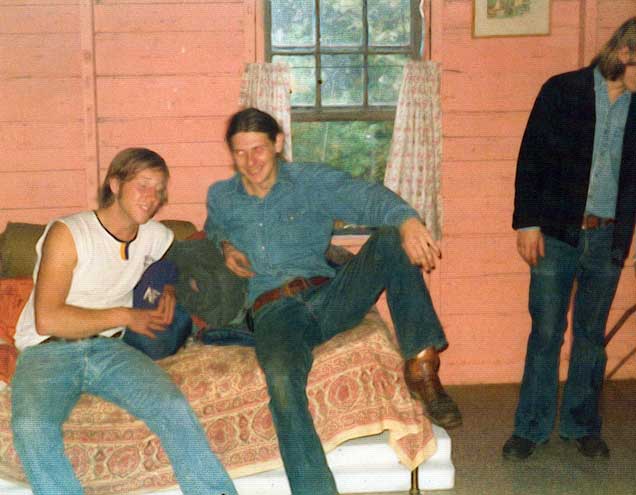

Ted and his sibs in Topsail Beach, NC

A visit to Manasota Key, FL

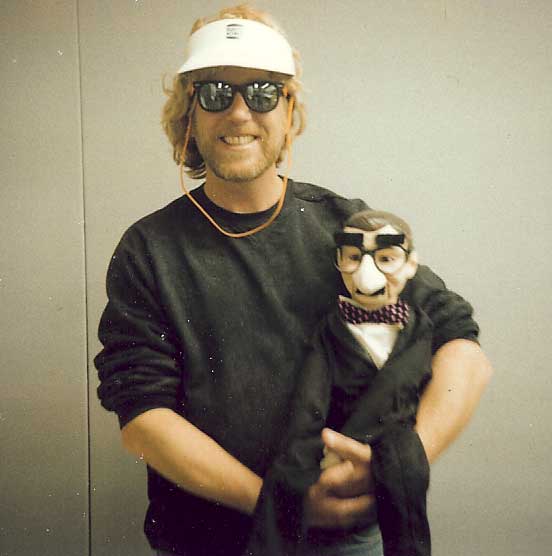

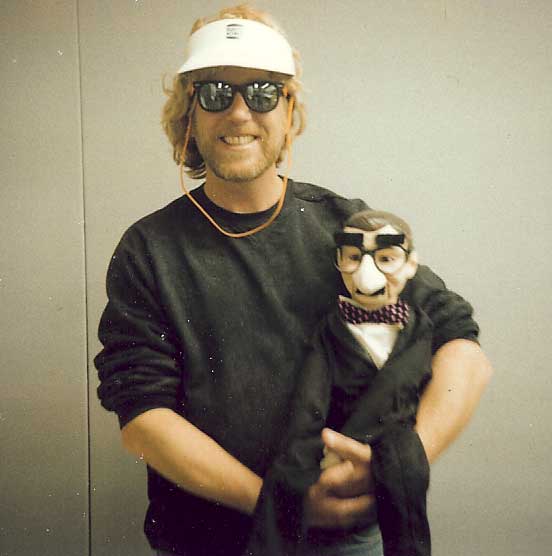

Ted and his “son” Woody, circa 1986

The remembrance for Ted at his favorite watering hole in San Francisco, Blooms Saloon

Article by Rick Ohler, East Aurora Advertiser

The old Sunday school lesson, “Pride goeth before a fall,” popped into my head when I realized that the brilliant column I was going to write this week wouldn’t work.

You see, I set about writing a pre-death, non-obituary for my friend Teddy Nichols. Even occasional readers of this space will know his name. Teddy has appeared in probably 60 of my 445 “View From Right Field” columns.

Teddy—Edward Joseph Maximillian Babalooey Nichols—is my first friend. My earliest memory of him goes back to 1954 or ’55 when we lived at 472 Oakwood and he lived at 461. It was a Saturday morning and we piled into Dad’s Rambler station wagon from Nelson A. Holmes & Sons on Ocean Road and made the short trip to Griggs & Ball. As part of their empire at the time, G & B had a yard across Riley Street where they sold gravel, corn, hay, straw and sand. I remember helping to fill bushel baskets with sand, hefting them into the Rambler and heading home to make a sandbox.

We played in the sandbox forever, well, until we could venture to Hamlin Park, one block away, or to the Boys Club, just a quick trespass through the Immaculate Conception Church parking lot, behind the convent (with nuns often chasing us) and over the fence at Aurora Motors’ body shop.

We were hardly a matched set, Teddy and me: I was the straighter of our duo; he was a smart aleck, practical joker, schmoozer of ladies and troublemaker who knew how to pick the wrong time to say the wrong thing. Together more often than not, though, we played touch football, mumblety-peg with jackknives; we learned about poker and losing our allowances to big kids, about the coolness of smoking cigarettes, about the joy of having a license, about beer and how to circumvent the legal age laws, about girls—well, he did, anyway. We double-dated, visited each other at college, smoked some funny cigarettes, then stayed in touch as he left for San Francisco and I stayed in the old hometown. Heck, our friendship is so old, we occasionally wrote letters, on paper, sent in envelopes to which we affixed a stamp and dropped in a mailbox. That is when we weren’t scamming the phone company to make free long-distance calls. We marveled at each other’s choices, when, in retirement, I became a newspaper writer and he became a three-dimensional artist creating wonderful, clever, fanciful, naughty pieces that delighted his hometown pals and San Franciscans alike.

Often playing Eddie Haskell to my Beaver when addressing my parents in our teenage years, he could affect a goody-two-shoes persona, even though he was the consummate smart ass and trickster, whom his classmates voted Most Mischievous in the 1968 senior poll. One time, maybe in 1960 or so, I was wearing a brand new shirt from Major’s Men & Boys Wear. Down at Hamlin, Teddy rushed up and offered a can of cherry pop he had bought me. What a friend. That’s what I thought until I began drinking and realized he had put a tiny hole in the can that delivered a stream of cherry liquid onto the front of my new shirt. When, as a Boy Scout, decked out in official BSA neckerchief, heavily be-patched shirt, olive shorts, knee socks and garters, I marched in Memorial Day parades, concentrating on my hut-two-three-four precision steps, Teddy, no Boy Scout he, would ride up beside me on his Huffy and call out, “three, six, 26, 18, not your left, your right, right.” I loved him and hated him all in the same day.

Two years ago, Ted was diagnosed with cancer. For a while, he submitted to treatments and put up a brave front, continuing to work on his creations and letting us know that calling himself an artist was his greatest comfort. But, as cancer does, it began to conquer Ted’s body, despite the sturdiness of his soul. On March 8, his college pal, Jimmy Mulligan, raced out to California, and on March 16 loaded Teddy into an airplane and installed him, with Hospice’s help, at Jim and wife Noelle’s Florida home, where he could die with friends, with dignity, in comfort.

Bob Herrmann, Ted’s and my friend of second-longest standing at 59 years and counting, and I decided that we would fly to see him in his final days. Then I would write him a pre-death, we-loved-you-when-you-were-alive obituary and surprise him in this issue of the Advertiser, which he has subscribed to his entire life. I phoned Ted on March 22, assured him we were on our way and welcomed his cheerfulness at the prospect of our arrival.

Our plane lifted off at 3:12 on the 23th. At 6:30, we landed, turned on our phones to discover that Ted had died at 3:15. He will never read this non-obituary, or the obituary I will write for the Advertiser soon.

I’ve shed a waterfall of tears over my buddy, but then I chuckle and ask, “Who else would drag me down to Florida, in a hurry, only to stand me up when I arrived? One final prank.”